The more you work your heart and lungs, the more efficient they become at delivering oxygen to the body and brain. With increased blood flow come the chemical cascades that may very well be your fountain of youth.

As we age smoking, inactivity, and eating poorly are root causes of disease. Lifestyle also influences the mental hazards that come with getting older. “The same things that kill the body kill the brain” states Dr. Mark Mattson, of the National Institute on Aging. Diabetes increases the risk of developing dementia by 65 percent, and high cholesterol increases the likelihood by 46 percent. The good news is that medical proof shows how exercise protects against these diseases. Yet, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) estimates about a third of the population over sixty-five does not engage in exercise or leisure activity.

Getting older is unavoidable, but falling apart is not. Understanding how exercise can protect the mind will lend a new incentive to get moving. The same factors that reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes also reduce the risk of age-related neurodegenerative disorders. The mental and physical diseases we face in old age are tied together through the cardiovascular and metabolic systems.

As we age, the cells throughout the body gradually lose their ability to adapt to stress. Older cells have a lower threshold for combating free radicals, excessive energy demands, and over excitability. The genes responsible for producing the “clean up” of damaging waste stop working, but exercising can halt and reverse that process. Exercise sparks the connections and growth among brain cell networks and encourages neuronal activity and neuro genesis. Yes, you do grow new brain cells. Exercise is like medicine, its a preventative and an antidote. As author Dr. John Ratey says in his book, Spark, the Revolutionary New Science of Exercise and the Brain, “Age happens, but you can definitely do something about the how and the when.”

Long before the benefits of scientific proof, natural healers fixated on three rules of a healthy lifestyle: exercise, eat right and learn something every day. The prescription for living a rich life hasn’t changed much, but now we know why

Eat right and eat light. Consuming fewer calories is a proven way to live longer with better brain power. A study in monkeys that began 18 years ago in the experimental gerontology lab at the National Institute on Aging suggests that a restricted caloric diet showed fewer markers of oxidative stress and inflammation in their blood. People over 50 should be careful about malnourishment because they’re losing muscle and bone mass anyway, but being overweight may inflict damage to the brain.

Balance your meals with whole grains, proteins, and dietary fats. Low-carb diets may help you lose weight, but they’re not good for your brain. Not to be mistaken for refined sugar and grains, but complex carbohydrates supply a steady flow of energy rather than the spike and crash of simple sugars, and they are necessary to transport amino acids such as tryptophan to the brain. Tryptophan is a precursor for the production of serotonin, which helps to keep brain activity under control. The brain is made of 50 percent fat, so fats are important too as long as they’re the right kind. Omega 3’s lower blood pressure, LDL cholesterol, and reduce neuronal inflammation. They elevate the immune response and increase proteins that enhance brain cell activity. Red or sock-eye salmon, cod, and mackerel are enormously beneficial as well as chia seeds and flaxseed oil. 15 minutes a day of vitamin D from the sun and nutrient rich foods containing calcium as well as B vitamins with folate improves memory and processing speed. Consult a doctor with a dietary background before supplementing and don’t assume your regular doctor is an expert in nutrition. Ask questions, maybe you need to locate a dietitian or nutritionist on your own. If your doctor doesn’t look healthy, that would be a good indicator.

Exercise is good for your brain. In addition to learning, exercise has shown to reduce or reverse the effects on aging. Exercise will help retain and access all the wisdom that’s been gathered along the way.

The average 76 year old has at least 3 chronic diseases and takes at least 5 prescription medications according to the CDC. Among those over 65, most suffer from hyper tension, more than two-thirds are overweight; and nearly 20 percent have diabetes. To compound matters, diabetes triples the chances of developing heart disease. There is also cancer and stroke and together these three diseases are the leading killers in thisage group.

The measures that control diabetes, also balance insulin levels in the brain and protects neurons against metabolic stress. The same aerobic exercise that lowers blood pressure and strengthens the heart also keeps capillaries in the brain from collapsing or corroding. Similarly, the way lifting weights prevents osteoporosis from devouring bones; resistance training also releases growth factors that makes brain cells bloom. Ratey calls it “Miracle Grow” for the brain. Another coincidence is that taking omega 3 fatty acids known for boosting brain acuity, strengthens bones as well. Bottom line: exercise guards against physical degeneration and improves cognitive functioning.

Exercise also improves responses to stress, which is actually a necessary thing, in the right amount says Dr. Ratey. “Neurons (brain cells) get broken down during a stress response, but like muscles, mild stress with time for recovery, makes neuro-pathways more resilient.

Exercise is good for learning. Why would this be? Because human biology evolved for the life of the hunter-gatherer. In other words, learning how and where to find sustenance required brain power and physical activity. Even now the relationship between food, physical activity, and learning is hardwired into the brains circuitry. You know by now that exercise causes your neurons to connect, while mental stimulation allows your brain to cruise on those neurons like a new highway. It’s no coincidence that studies show the more you engage the brain, the more likely you are to hang onto your cognitive abilities and stave off dementia. It’s not so much about the diploma; it’s about being interested in learning.

A particularly important effect of exercise for mature adults, is that it sparks dopamine; which rallies motivation and reward systems. Dopamine diminishes with age. When you get your blood pumping enough, the capillaries feeding the brain cells thrive. Oxygen, fuel, growth factors and repair molecules are carried by the bloodstream. The production of neurotransmitters like dopamine and serotonin regulate moods, impulses, attention and satisfaction. So, if you have an important afternoon brainstorming session scheduled, going for a brisk walk or short intense run during lunchtime is a smart idea. Better yet, combine your aerobic activity with a “skill acquisition” such as inventing a new coordinated movement while you’re out walking or running because it has even more beneficial effects on the brain. It enriches memory and experience storage and accesses learning mechanisms.

Population studies support the evidence that exercise holds off dementia. In one, about fifteen hundred people from Finland originally surveyed in the early 1970’s were contacted again twenty-one year years later, when they were between sixty five and seventy-nine years old. Those who had exercised at least twice a week were 50 percent less likely to have dementia. What’s particularly interesting is that the relationship between regular activity and the onset of dementia was even more pronounced among those carrying a predisposition gene. The researchers suggested that the one explanation might be that their brain’s neuro-protective systems are naturally compromised by the gene variant, making lifestyle particularly important for the brain’s ability to compensate for damage by recruiting other areas to help with tasks.

Statistics also show a relationship between social contact and mortality. Social experiences demand more from your brain, and builds stronger neuronal connections, more brain cells increase the ability to compensate for age related decline.

How Much Exercise? Your overall strategy should include four areas: aerobic capacity, strength, balance and flexibility. Consult with a medical professional or trainer who knows your history, but here are some solid guidelines:

Aerobic: 4 days a week, varying from 40 minutes to 1 hour at 60 to 65% of your maximum heart rate. At this level, you’ll be burning fat in the body and generating the ingredients necessary for all the structural changes in the brain. Walking should be adequate, but try more intense walking twice a week at 70% MHR for 20 to 30 minutes.

Strength: Weight resistance machines or free weights twice a week, 3 sets of 12 to 13 repetitions. This is critical for preventing and counteracting osteoporosis. Activities that involve bouncing or jumping also help strengthen your bones: tennis, dancing, aerobic class, jumping rope, basketball, and, of course, jogging or running.

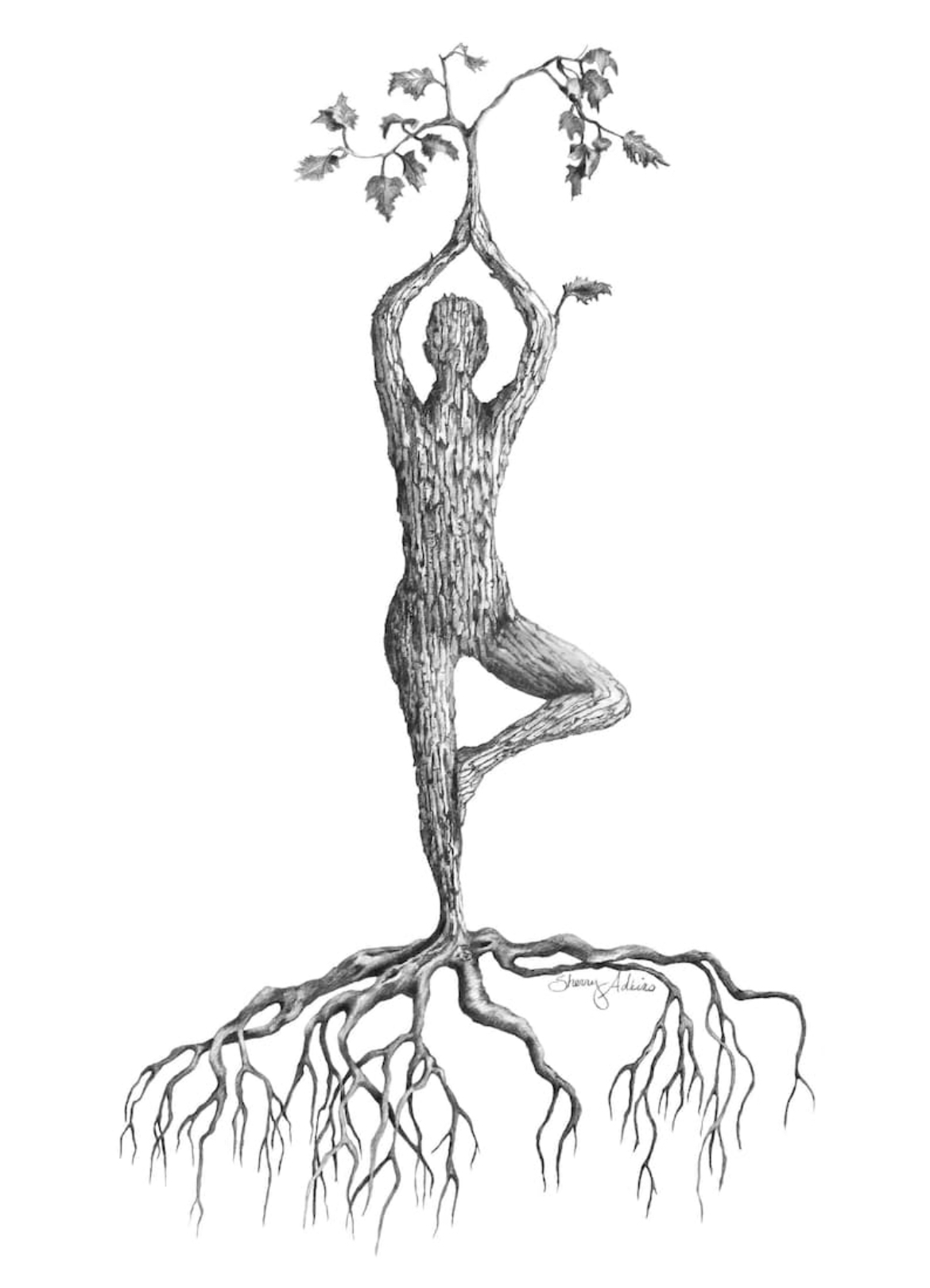

Balance and Flexibility: Yoga can be done daily for 30 minutes or 1.5 hours twice weekly. Tai chi, martial arts, and dance all involve balance and flexibility skills, which are important to staying agile.

Note on Yoga: It’s your full service mind/body “preservation station.” The intensity can range from relaxing and mild to very gymnastic. This can be accommodated by a variety of different styles of yoga and it is up to the practitioner to choose which style will best suit their needs at any given time. The aerobic aspect involves the speed in which the postures flow. There are the balancing poses to challenge brain function and the various types of weight bearing postures designed to build bone mass and eventually hold one’s own body weight. Flexibility strategies found in yoga include:

Dynamic stretching: repetitive stretches setting muscle length to accommodate the activity since it was last performed. This can also include jumping or hopping as in the Ashtanga practice, but general Sun Salutations is a good example.

Passive stretching: using body weight, gravity and synergistic muscle groups to create the stretch like Iyengar based yoga. Poses that are held for longer periods allow the stretch receptors in the muscles to acclimate and helps the “fascial sheath” to lengthen.

Facilitated stretching: involves briefly contracting the muscle and letting go. The “slack” created by this response is then taken up by deepening the stretch. Facilitated stretching is an example of yoga’s philosophy of “uniting opposing forces” similar to isometrics. This type of stretching is incorporated across many styles such as Bikram yoga, and other various forms associated with power yoga or alignment based yoga.

As a bonus, yoga includes breathing practices that are intended to bring awareness to the autonomic nervous system and encourage greater control over one’s emotions via the breath. Meditation offers an uncomplicated method of relaxing a busy mind and accessing the quiet place within. In this way, focus and concentration are further cultivated.

In a nutshell, mild and controlled stress as in exercise is a good thing. The same work-out that’s intended for physical fitness, applies to cognitive function. The body and brain need to be challenged, and provided that there’s a recovery period and time to repair, both the body and brain, strengthen and grow.

Don’t get down on yourself if you don’t like to exercise though, you may be genetically predisposed to disliking it. A 2006 European study showed that gene variations have an impact on whether you enjoy the feeling of exercise. People with this dopamine variation may have “reward deficiency syndrome,” so the mood improving mechanism could be sluggish. Try to find an activity that is manageable and stay with it. The aspect of self-discipline in itself has a plethera of rewards.

Exercise prepares neurons to connect, while mental stimulation allows your brain to capitalize on those fresh cells. Remember, the brain can be rewired by taking action! Get a personal trainer who can help you stay on track, inspire and motivate you. Exercise immediately increases levels of dopamine, and if you stay on some sort of schedule you may literally “change your mind.”